Once upon a time, in a land far, far away . . .

Cavemen—and women!—waged a battle against unwanted (body!) hair . . . much as we do today!

Hard to believe? Absolutely! True? Evidently. At least that’s the consensus, based on Stone Age cave paintings depicting such scenes as cavemen using seashells as tweezers!

And that’s not the only method that ancient man devised for hair removal: Word has it that flint, stones, and other materials were sharpened and used to “scrape away” hair.

Yes, my friends, it seems that the war against unwanted body hair has been waging for quite some time!

Woven throughout the backdrop of history, it’s the tale of how man has viewed—and responded to—the hairiest of situations.

Let’s take a look at some of history’s hair removal milestones!

Stone-Age Resolve

Stone Age man was nothing, if not resourceful. These “first responders” were true trailblazers on the front lines of hair removal.

Archeologists believe that ancient man (as far back as 30,000 B.C.!) sought ways to remove body hair. First, by fashioning rudimentary “razors” (aka “scraping tools”) by sharpening such materials as flint, stones and shells; and later by positioning two seashells into an instrument for grabbing (or “tweezing”).

Seashell tweezers proved so popular that ancient cavemen immortalized them in their cave paintings—which is how we know about them today!

We can only surmise what drove prehistoric man toward a smoother, sleeker look. Many believe it was simply a matter of survival: Less hair meant one less appendage for a (hungry!) prehistoric beast to grab; and less hair meant one less place in which insects and other varmints (e.g., lice and mites) could nest or hide.

We can only surmise what drove prehistoric man toward a smoother, sleeker look. Many believe it was simply a matter of survival: Less hair meant one less appendage for a (hungry!) prehistoric beast to grab; and less hair meant one less place in which insects and other varmints (e.g., lice and mites) could nest or hide.

Survival of the Fittest may have been closely related to Survival of the Smoothest!

Look Like an Egyptian

Although Egyptians didn’t start the battle against unwanted body hair, they certainly took it to a whole new level. After all, who hasn’t seen pictures of ancient Egyptians all smooth and hair free?

To them, hairlessness was more than a means of creating a cooler body temperature to combat the hot Egyptian days or removing a possible breeding ground for irritating West Nile critters. It was a reflection of one’s status, sophistication and nobility.

Deemed shameful and unclean by Egyptian priests—who even shaved off their eyebrows and removed their eyelashes—body hair was something the well-bred Egyptian fought diligently to remove. After all, hair belonged on animals . . . and lesser classes!

Although the typical Egyptian

Although the typical Egyptian drew the line at shaving eyebrows and plucking eyelashes, the quest to rid oneself of body hair was of such importance that it’s no wonder that barbers were highly esteemed professionals. Indeed . . . Some members of the upper class even kept a personal barber on their household staff.

And Egyptian kings, ever concerned about maintaining their hairless state in the afterlife, often arranged for their trusty barber—along with a sanctified, jewel-encrusted razor—to be buried alongside them so daily shaves could continue uninterrupted.

But being hairless and looking hairless were two different things. Although Egyptian men and women often sported shaved heads, they typically wore elaborate wigs when they went outdoors or attended social functions. Such wigs, often comprised of human hair or flax woven into a mesh cap and affixed with beeswax, provided a cooler and more sanitary environment than their own hair and always looked beautiful—unlike the socially frowned upon state of graying or balding hair.

Even children sported semi-shaved heads. Children’s heads were shaved to create a “sidelock of youth,” a long plaited wick of hair left on an otherwise bald head. Such wicks were maintained until puberty—for boys, that meant until they were circumcised, usually at the age of 14.

Although beards, like all facial hair, were frowned upon in sophisticated circles, there were exceptions: As beards were considered an attribute of the gods, it was only fitting that Egypt’s pharaohs (considered gods themselves) sported (fake!) beards on special occasions.

Ancient paintings and artifacts reveal a number of ways in which ancient Egyptians rid themselves of body hair: They utilized such tools as hooked-handled razors made of bronze, copper or gold

; bronze tweezers

; and pumice stones

(for scraping); as well as methods like body sugaring (the application of a sticky paste, such as bees wax, that was applied and yanked off via a strip of cloth), which appeared around 60 B.C. and was embraced by Cleopatra herself; threading; and depilatory pastes made from abrasives like arsenic and quicklime (a key ingredient in cement!).

Mesopotamia’s (Mini) Hair-Removal Mania

Although Mesopotamia can’t compete with ancient Egypt’s obsessive devotion to living hairfree, this ancient society (founded before Egypt and considered a cradle of civilization), nevertheless, put a premium on hair removal.

Early writings tell of kings requesting that the women presented to them be “clean and smooth” and ancient art—like a carving of a naked Mesopotamian goddess known as Ianna Ishtar—show a marked lack of hair from the neck down.

Early writings tell of kings requesting that the women presented to them be “clean and smooth” and ancient art—like a carving of a naked Mesopotamian goddess known as Ianna Ishtar—show a marked lack of hair from the neck down.

Although views on hair differed throughout Mesopotamia’s various eras, hair removal was important enough for the barbering profession to be held in high esteem—similar to that of doctors and other luminaries. Indeed. Throughout much of its history, men kept their faces shaven, and priests typically shaved their heads.

Of course, Mesopotamian barbers were known to do more than remove unwanted hair. While “priest-physicians” focused their services on the upper class, it was the barbers—known as gallabu—who served the common man by performing surgeries, branding slaves, extracting teeth, and the like.

Indeed. The description for a “surgeon’s knife”—a naglabu—could be expressed by combining the pictorgraphs for “barber” and “knife.”

Located in what now comprises modern-day Iraq and parts of Syria, Turkey and Iran, Mesopotamian towns often had a street or area where barber shops were located.

But as for “doctoring duties,” barbers also bore responsibility for their services. In the Code of Hammurabi, which contained 282 laws for ancient life, there are multiple mentions governing barbers.

No 226 states that any barber who removes a “slave’s mark” (assuming it’s without the owner’s knowledge and done to make the slave untraceable), shall have his forehead cut off.

Barbering, it seems, was serious business in ancient Mesopotamia!

Thankfully, barbers also kept busy with less risky behavior, such as the creation of rudimentary shaving creams using ingredients like animal fat and wood alkali to prepare the beard for shaving.

Archeological evidence also suggests that tweezing and body sugaring were used as hair removal methods by ancient Mesopotamians.

Ancient Romans

“Real Men Shave” might have been an apt saying throughout much of ancient Rome’s history. Indeed. One of a teenage boy’s most important rites of passage occurred when he officially ushered in his manhood by performing his first shave in front of family and friends at a festive gathering thrown in his honor.

This rite of passage was so revered that the facial hairs produced by this first shaving were placed in a special box—golden and pearl-studded in the case of the Emperor Nero—and consecrated to a Roman deity.

So important was a clean shave, that beards were reserved for slaves, servants and barbarians.

Barbers—or tonsors, as they were called—became permanent fixtures in many wealthy households; and part of the commercial scene for other, less-wealthy men, who frequented their local barbershop (or tonstrina).

Unfortunately, the challenge of maintaining sharp razors (or novacila) proved too much for many barbers, whose dull tools delivered their share of nicks and cuts—a situation described by one ancient writer who implicated the barber Antiochus in his own chin scarring.

Unfortunately, the challenge of maintaining sharp razors (or novacila) proved too much for many barbers, whose dull tools delivered their share of nicks and cuts—a situation described by one ancient writer who implicated the barber Antiochus in his own chin scarring.

Despite the adherence to a clean-shaven look, ancient fashion trends proved fickle, as Roman men followed the look set by those in power. For example, Roman men used tweezers to pluck their facial hairs on a daily basis in 50 B.C., as per Julius Caesar, but embraced beards as a new fashion trend 150 years later, when Emperor Hadrian, hoping to hide some unsightly facial blemishes, sported a long beard. Beards stayed in vogue until the reign of Constantine the Great, and then enjoyed a resurgence in popularity at the start of the 7th Century.

Of course, men weren’t the only ones looking for a cleaner look. Women of means, who viewed hair removal as a sign of upper class, utilized pumice stones, razors, tweezers and depilatory creams—containing such ingredients as resin, pitch, ass’s fat, ivy gum and bat’s blood—as well as the technique of threading to rid themselves of unwanted body hair.

Unlike their Egyptian counterparts, ancient Romans were not keen on the removal of all body hair, and may have even viewed such body baldness as grotesque.

Not even Emperor Elagabalus, who came to power in 218 A.D. at the age of 15, and practiced full-body hair removal (along with wearing women’s clothing and makeup), could sway Roman men to the other side. Indeed. Elagabalus proved a short-lived ruler, when he was, shall we say, taken out by his own guards after only four years in power.

Ancient Greeks

Although initially a symbol of maturity and manhood in ancient Greece, beards went out of vogue during the time of Alexander the Great, who took the throne in 336 B.C.

As a great military tactician, Alexander the Great saw the disadvantage of long, flowing beards on the battlefield—they were a little too easy to grab!—and strictly forbid his soldiers to sport them. Clean-shaven faces (and closely cropped hair) were the de rigueur look of the day.

Before that time, however, beards were quite the rage. Greek boys forewent their first haircut until their first beard started to grow; and then dedicated their first beard to the “sun god” Apollo in a religious ritual.

As for Greek men, beards were cut to show mourning or grief; or to indicate shame or punishment, as was the case among the Spartans, who would shave off half of a man’s beard to indicate cowardice in battle.

As for Greek men, beards were cut to show mourning or grief; or to indicate shame or punishment, as was the case among the Spartans, who would shave off half of a man’s beard to indicate cowardice in battle.

Barber shops became so popular that their services spread beyond hair care to that of offering a gathering place for the discussion of sports and politics.

The importance of removing additional body hair also became fashionable as young, hairless athletes came to represent an aesthetic ideal.

As for women, it’s believed that they practiced full-body hair removal via body sugaring, with the exception of the head, eyebrows and eyelashes. This belief in such full-on hair removal is supported by Ancient Greek statues that show smooth, hairless female bodies.

In addition to shaving and body sugaring, ancient Greeks are believed to have used tweezers, cream depilatories, “scraping” stones, as well as fire for singing, in the battle against unwanted hair.

The Middle Ages and Thereabouts

Ever notice how women featured in portraits from the Middle Ages seem to have unrealistically high, smooth—hair free—foreheads? Ever wonder why?

Perhaps you chalked it up to a long-lost genetic trait, or a family gene that ran rampant at the time. Perhaps you’d earn credit for creative thinking—but not for guessing correctly.

Perhaps you chalked it up to a long-lost genetic trait, or a family gene that ran rampant at the time. Perhaps you’d earn credit for creative thinking—but not for guessing correctly.

The reason, of course, is because the Middle Ages ushered in an era rife with strange hair fetishes—like the one that involved women plucking their eyelashes and eyebrows.

One of the most recognizable looks of the day was–you guessed it!—the “high forehead” that many a trend-conscious woman embarked on wholeheartedly and elevated to the realm of high fashion. It seems that forehead plucking was the price one paid for achieving a truly aristocratic look.

And who better to illustrate this look than Queen Elizabeth I, whose reign from 1558-to-1603 placed her at the forefront of this fashion. Indeed. Many followed her example of removing all hair from the face, forehead and eyebrows.

The look was so accepted that many mothers rubbed walnut oil –or concoctions made from such ingredients as vinegar and cat’s dung—into their children’s foreheads in hopes of preventing hair growth . . . and lifelong plucking!

But why stop at one’s forehead? At various times throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, women willingly shaved their heads—all in the name of high fashion. It was simply easier to accommodate the elaborate wigs and headpieces popular at the time without long, bulky hair getting in the way.

As for non-facial hair, women didn’t shave their legs or armpits, although some sources site a different story when it comes to more private hair. Catherine de Medici, who became the Queen of France in the mid-1500s, strictly forbid her ladies in waiting to remove their pubic hair; although such practices prevailed in other parts of Europe until England’s Queen Victoria ushered in more conservative views during her reign, which began in 1837. But even then, it’s believed that the practice prevailed privately, especially among the upper classes.

One humorous anecdote is found in a letter that Horace Walpole wrote in 1755, which comments on the retirement of the Duke of Newcastle, who was said to have paid 430 pounds to have his wife’s facial hair permanently removed. Evidently questioning the efficacy of such treatment, Walpole states that the newly retired Duke can now “let his beard grow as long as his Duchess’s.” Ouch!

Read All About It… The Quest for a Safe Shave!

Despite shaving’s prevalence throughout history, typical razors (with their long, sharp blades!) proved treacherous in all but the most skillful of hands. (Professional barber, anyone?) It wasn’t until 1769 that a Parisian master cutler named Jean Jacques Perret addressed the topic of designing a less dangerous razor in a self-help book he wrote and titled La Pogonotomie, or The Art of Shaving Oneself.

Indeed. Perret, an expert in the fabrication of sword blades, surgical instruments and razors (who would present King Louis XVI with razors and a mirror of cast steel in later years), is credited with creating the first safety razor, which he actually did a few years earlier, in 1762. Although he never patented the idea, he did make and sell his product.

Inspired by a carpenter’s plane, Perret’s razor relied on a wooden sleeve to partially enclose the blade of his era’s long, folding, straight razor, so that only a portion—just enough to provide a nice shave—was exposed. Deep neck and facial wounds, take note!

Courtesy of Mauro Lorenzi

Less than a hundred years later, in 1847, an Englishman named William Henson ushered in another shaving milestone when he questioned the fundamental shape of the era’s still prevalent straight razor by filing a patent for a T- or rake- shaped razor. The shape, which he likened to that of a common garden hoe, proved a winner. It’s the shape we still use today!

But while Perret and Henson’s designs delivered substantial safety improvements, they were only the first in a long line of contenders.

In the United States alone, about 120 U.S. patents were filed targeting razor safety from 1864 to late 1901.

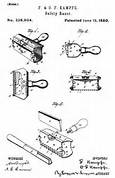

One such patent was filed in May of 1880 by Frederick and Otto Kampfe of Brooklyn, New York, two German brothers who had immigrated to the United States and set up a cutlery business, along with a third brother, Richard.

Their design, based on the hoe-shape outlined by Henson, utilized a “blade holder,” which was attached to the handle, thus separating the blade and the handle. This was markedly different from Henson’s design, in which each blade had a tapped hole into which the handle was screwed. The Kampfe design also included metal clips for holding the blades in place; a “plate” with “bars or teeth” for protecting the skin; and a razor frame that also functioned as a “lather catcher.”

While some credit the Kampfe brothers with designing the first safety razor (as opposed to Perret), one thing is certain: Their razor, dubbed the Star Safety Razor, was a resounding success . . . and their patent application earned the distinction as the first to use (actually, coin!) the term “safety razor”—although whether this was the result of deliberate wordsmanship or simple happenchance is open to debate!

Success aside, Kampfe’s Star Razor had at least one major drawback: Its steel blades, although meant to last, still needed stropping and honing to retain their tip-top shape. While this time-consuming, skill-requiring endeavor was nothing new for shavers, it proved to be a task ripe for inventiveness.

And inventiveness came. Twenty-one years later, a salesman with the grand name of King Camp Gillette filed a U.S. patent on December 3, 1901, featuring a flexible, double-edge disposable blade . . . and just like that, the modern era of safe, convenient shaving had arrived.

Although Gillette’s (given) name may have been a boon, a bit of irony can be found in the (sur) name of the product’s co-inventor . . . William Emery Nickerson. One can only wonder why his name wasn’t lauded more by the company!

Although Gillette’s (given) name may have been a boon, a bit of irony can be found in the (sur) name of the product’s co-inventor . . . William Emery Nickerson. One can only wonder why his name wasn’t lauded more by the company!

Still, Gillette and Nickerson are credited with bringing to market the personal shaving world’s first disposable razor blade system. The idea, which was the brainchild of Gillette, didn’t become a reality until Nickerson, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) engineer, discovered a way to mass-produce thin, inexpensive, disposable blades of stamped steel.

The company they founded on September 28, 1901, as the American Safety Razor Company, was renamed The Gillette Safety Razor Company a year later in July 1902. Manufacturing began in 1903 and one year later, in 1904, Gillette’s original patent—No. 775,134—was granted. The rest, as they say, is shaving history!

And what a history it’s been!

Gillette expanded his customer base tremendously during World War I when he struck a deal with the U.S. Armed Forces to provide safety razors and blades to enlisted men. The government’s order put 3.5 million Gillette razors and 36 million Gillette blades in the hands of America’s soldiers (future civilian customers!) and prompted the hiring of an additional 500 to the Gillette workforce.

And what better way to carry the Gillette name overseas? European soldiers, envious of the shaving kits carried by their American counterparts, sought their own Gillette razors, thus propelling Gillette’s European sales to new heights.

By 1915, the shaving industry had set its sights on women as a way of expanding the ever-popular shaving category. Gillette introduced the first women’s razor, called the Milady DeColletee, and the fashion world began making its case (or that of its sponsors!) that female bodies were more beautiful with less hair!

Among the milestones was a photograph in Harper’s Bazaaar magazine that featured a model wearing a sleeveless dress and sporting smooth (hairless!) underarms; and a campaign launched by the British razor manufacturer Wilkinson Sword Company declaring that underarm hair on women was neither feminine nor hygienic. Razor sales doubled in less than two years!

When the roaring 1920s came roaring in, women were ready to flaunt smooth underarms and legs in the day’s skin-baring fashions.

While Gillette’s breakthrough shaving system heralded the beginning of simpler, safer, shaving for the common man (and woman!), improvements were still on the horizon. Creative minds, it seems, wouldn’t rest until shaving was at its best.

People like U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel Jacob Schick, whose 1926 repeating-rifle-inspired razor stored replacement blades in the shaver’s handle and loaded them semi-automatically, joined the ranks of shaving history—and lent his name to one of the industry’s most successful brands.

Quite the visionary, Schick’s quest for better shaving continued. Two years later, in 1928, he patented the first electric dry shaver and became so convinced that it represented shaving’s future that he sold his interests in the “repeating-rifle” razor company and formed a new company to manufacture and sell Schick electric razors.

The Gillette company also continued its inventive streak with the 1946 introduction of its Blue Blade Dispenser, which protected exposed fingers by eliminating the need to unwrap blades; and Wilkinson Sword ushered in the era of stainless steel razor blades in the early-to-mid 1960s, thus bidding farewell to the prevalence of rust-prone carbon steel razors, which often required daily changing.

The 1970s proved a decade of even greater change. In addition to the debut of the first multi-blade razor (for a closer than ever shave!), Wilkinson Sword introduced the first disposable plastic cartridge, all but eliminating finger cuts. Not to be outdone, Bic followed the act with a crowning achievement in 1974—the first fully disposable razor.

Shaving, it seems, was safer than ever!

The Modern Age of Hair Removal

Hair removal has continued to play an important role in personal grooming throughout the modern era, with women (and men!) embracing everything from the most simple, tried and true methods (like shaving!) to the most scientifically advanced ones to rid themselves of unwanted body hair.

Electrolysis

One of the most effective methods of hair removal traces its roots to October 1875, when Charles Michel, a St. Louis ophthalmologist, announced that he had found a way to treat trichiasis, an often painful, chronic condition caused by ingrown eyelashes.

After years of experimenting, Michel claimed to have found success several years earlier, in 1869, by inserting an electrified needle down a hair follicle shaft and holding it for several minutes. The result was just what the doctor ordered . . . a hair that never grew back!

His treatment, which resulted in the destruction of the hair follicle’s growth cells, is still around today. It’s called electrolysis!

Interestingly, it was a chemical reaction triggered by the electricity, not the electricity, itself, that destroyed the growth cells. The electricity altered the pH of the hair shaft from a neutral to a highly caustic state (converting a body salt into lye), thus creating a chemical strong enough to destroy everything in its path. In this case, an unwanted hair!

Interestingly, it was a chemical reaction triggered by the electricity, not the electricity, itself, that destroyed the growth cells. The electricity altered the pH of the hair shaft from a neutral to a highly caustic state (converting a body salt into lye), thus creating a chemical strong enough to destroy everything in its path. In this case, an unwanted hair!

Dr. Michel’s invention proved well-timed. Two years after reporting his findings, the newly formed American Dermatological Association became the first medical organization to categorize excessive female hair as a pathological state, calling it hypertrichosis. There was no denying it . . . Body hair was serious business!

Michel’s method of electrolysis, called the Galvanic method, remained the sole method of use for almost 50 years, until Henri Bordier, a doctor from Lyon, France, introduced an alternative method called Thermolysis (also known as Shortwave, Diathermy, High Frequency, Radio Frequency and Alternating Current) in 1924.

Unlike Michel’s method, which relied on a chemical reaction, Bordier’s method relied on a low intensity, high-frequency electrical current to destroy hair cells via heat. This new method proved far speedier than its predecessor, treating eight-to-10 hair follicles per minute, but came with a drawback: It wasn’t as effective.

As such, a third method entered the fray in 1948, when a U.S. patent was granted to the St. Pierre Epilator Company Inc. for a machine offering a “blended” or “dual action” technique. Developed by Arthur Hinkel and Henri St. Pierre, the new device utilized a galvanic current and a low-intensity, high-frequency current simultaneously, thus borrowing from its two predecessors. The method was aptly named the Blend method.

Twenty years later, in 1968, Hinkel co-authored a book titled Electrolysis Thermolysis and the Blend: The Principles and Practice of Permanent Hair Removal, which widely publicized the Blend method and put forth a better scientific understanding of electrolysis.

Today, all three methods—the Galvanic, the Thermolysis and the Blend—remain in use, enhanced by such technological advancements as transistors, computerized controls, pre-sterilized and disposable needles, and the like.

Despite its humble beginnings, electrolysis remains a major weapon in today’s hair removal arsenal. It’s the only treatment recognized as delivering permanent hair removal by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (Lasers, while mighty in battle, have earned only the right to claim permanent hair reduction.)

X-Rays Gone Awry

One of the most tragic tales in the history of hair removal can be traced to the much celebrated discovery of x-rays—a form of electromagnetic radiation—by German physicist Wilhelm Roentgen.

Roentgen’s discovery, made on November 8, 1895, made the kind of news that quickly captured the world’s imagination. (After all, for the first time ever, man could see through flesh to the inner skeleton).

Cartoonists had a heyday with the concept, highlighting all sorts of hilarious scenarios; one enterprising company introduced lead panties to block prying eyes; and a university president wrote that x-rays might soon be used to read thoughts.

And doctors? They aimed their new machines at all sorts of things—cancers, tumors, eczema, acne . . . even their own hands.

Before long, an interesting side-effect of x-rays emerged: Hair loss!

In 1899, Leopold Freund, an Austrian doctor credited as the first to use x-rays in dermatology (he treated a hairy growth on a patient’s back in 1896), noted the following: “Hair begins to fall out in thick tufts when lightly grasped, or it is seen on the towel after the patient’s toilet.”

His verdict? “We possess in the Roentgen-treatment an absolutely painless method of epilation.”

Quick and painless, x-rays seemed poised to become the next big thing in hair removal. Success stories, like the “curing” of a “bearded lady” in Kentucky, only reinforced Freund’s belief.

Of course, no one fully understood the deadly and disfiguring effects of radiation. (After all, the full brunt of radiation can take years and even decades to emerge.) Those who did voice concerns—such as a number of French doctors whose patients had fallen ill—were often disregarded. Freund, himself, dismissed the concerns of the French doctors by citing the “hysterical character” of French patients.

Others, like Elizabeth Fleischmann, an enterprising young Californian who established an x-ray business within two years of Roentgen’s discovery, embraced the new technology to her detriment. By January 1905—less than 10 years after starting her highly successful operation—one of her arms was so severely damaged from x-ray exposure that it required amputation. She died seven months later.

Still, such red flags went largely unheeded. For Albert Geyser, a German immigrant who graduated from a New York medical school in 1895, x-rays held endless possibilities.

Although originally critical of using them for hair removal, he eventually changed his tune, believing their damaging effects could be tamed by better designed equipment and safer practices. (He certainly knew their dangers: Over-exposure had caused severe burns to the fingers on his left hand, which reportedly led to their amputation.)

Geyser, working as an instructor at New York’s Cornell Medical College, soon developed his own answer to the vexing problems that seemed to plague x-ray use: an invention he called the Cornell x-ray tube.

According to an April 12, 1908, New York Times article, the tube delivered x-rays to the treatment area only—a feat it accomplished by using “heavy lead glass” to contain the rays and a “flint glass window” to direct them to the area of need. In addition, the connecting wires were “encased in glass insulators to prevent sparking on any part of the patient while under treatment.”

The article was ambitiously titled, “New Tube Robs X-Ray of Danger,” and it helped send a message that the Cornell tube made x-rays as safe as safe could be. Indeed. The article described Geyser’s invention as “one of the most brilliant achievements attained in the domain of electro-therapeutics since the x-ray came into use as a healing agent.”

Geyser was just getting started. In 1915 he published an article in The Journal for Cutaneous Diseases in which he stated that “no protection of any kind, either for patient or operator” was needed when using the Cornell tube.

In 1920, an advertisement for a Philadelphia business mentioned the use of the Roebling Geyser Method—a likely reference to the Cornell tube, since Geyser’s son, Frank Roebling Geyser, a medical doctor, was known to work with his father.

In wasn’t until 1924, however, that the use of the Cornell tube began to explode. Geyser, along with others, formed the Tricho Sales Corporation to produce, lease and offer standardized training for x-ray machines featuring the Cornell tube.

Advertisements and promotional literature for the Tricho system abounded, extolling its safe and effective use. Claims of “Scientific-safe-sure” and “No scars or other injury to the most delicate skin” surely reassured potential clients, as did the assertion that “Tricho treatments have been given to wives, daughter and sisters of physicians.”

Soon, Tricho clinics were in more than 75 cities across the country. No medical training was required to operate the machine—only a few weeks of company training.

As for the treatment, clients simply sat at a mahogany cabinet, pressed the area to be treated against the small window that delivered the x-rays and waited for the operator to

Tricho System

flick a switch. A few moments later—with little more than a low hum to mark the interim—the machine shut itself off automatically. The session was over, and the client was free to book the next appointment. Clients typically submitted to a course of treatments—reportedly an average of 15-to-20—to achieve permanent hair removal.

Such courses typically cost anywhere from a few hundred dollars to more than a thousand—a price that failed to deter many of those troubled by excess hair. Indeed. The New York clinic, alone, boasted 20,000 clients—a sure sign of a lucrative business.

Trouble was brewing, however. In 1926, Ida Thomas of Brooklyn, who had submitted to hair removal treatments in 1920, brought a lawsuit against Frank Geyser for $100,739—the cost of her treatment, plus $100,000 in damages. Her complaint? The treatment had caused her skin to thicken and wrinkle.

Although her lawsuit didn’t garner much attention, the winds were shifting: Frank Geyser was arrested two years later following a similar complaint.

Soon, more and more former clients began stepping forward with troubling manifestations of damaged skin—wrinkles, lesions, ulcers and even cancerous areas. The truth was becoming undeniably evident. In July 1929, the American Medical Association condemned the treatment, and the Tricho Sales Corporation folded a year later.

Unfortunately, the x-ray machines used by Tricho—as well as similar ones—didn’t immediately disappear . . . and new ones even popped up. They became part of an underground where clients—sometimes unsuspecting—could still pay for quick and (temporarily) painless hair removal. One account says that such machines were in circulation “at least” into the 1950s.

Sadly, by 1970, x-ray hair removal was cited as the source of more than a third of all radiation-induced cancer in women over a 46-year-span—a tragic end to a once promising story.

Depilatories: Marvel-ously “Neet” “Veet”

Electrolysis isn’t the only hair removal method with modern roots in America’s heartland.

Although depilatories have been around since ancient times (arsenic and quicklime, anyone?) and advertisements touting their use for “superfluous hair” populate English and Colonial newspapers as far back as the 1700s, the category seems to have come into its own in the early 20th Century.

It was then that Edward Druin Frier, a Missouri native working at the Goodyear Rubber Company in Akron, Ohio, is said to have teamed with a French chemist (possibly a co-worker), to create a depilatory for women who wanted to wear the day’s skin-baring fashions without embarrassing body hair.

Like earlier depilatories, his would have worked by breaking the disulfide bonds that link the hair’s protein chains, thus causing the hair to weaken and disintegrate at, or just below, the skin’s surface.

In layman’s terms, you simply apply the product, wait a few minutes, and then wipe it—and that unsightly hair—away! No nicks! No cuts!

Although details surrounding Frier’s invention remain sketchy, one source identifies the product’s name as Marvel, and says its distribution, although successful, was initially limited to the Akron area. It wasn’t until 1918 that Frier, having returned to his home state of Missouri, formed a St. Louis corporation he called the Hannibal Pharmacal Company, and changed the product name to Neet.

Eleven years later, the company, renamed Neet, Inc., was listed on the New York Curb Exchange for an initial offering of more than $1.5 million—a small fortune at the time. Unfortunately, Frier was not alive to see this success. He had died three years earlier at the age of 40, due to poor health.

The saga of Neet, however, is not without its tales. Newspaper clippings of the day report multiple lawsuits—such as those brought by Frier’s widow and father-in-law against an ex-poultry expert named Rolla Cecil “R.C.” Lawry, who came to own (or control!) much, if not all, of the company.

It’s unclear when or how Lawry, a Missourian himself, became involved in the Hannibal Pharmacal Company. What is clear is that Neet ads dating as far back as 1928, celebrated him as the product inventor.

One full-page, 1928 ad features a headshot of Lawry, above a flurry of somewhat flowery text describing him as the product’s discoverer, from whose “fertile genius many important discoveries have come.”

The main headline declares, “Now! A New Way to Remove Arm and Leg Hair that Ends Bristly Re-Growth Forever and Delays All Re-Growth Indefinitely.”

A 1929 ad identifies him as the “noted beauty scientist, whose discovery is largely responsible for solving the arm and leg hair problem.”

Although research indicates that Lawry was not the product’s inventor, it’s possible that he did change the original formula, thus allowing him to justify such claims.

Lawry’s personal life was reported in no less than the New York Times in late 1930 when, less than two weeks after ending his 18-year marriage, the 46-year-old, described as the “millionaire president of Neet, Inc.,” wed a 24-year-old former telephone operator for the Hannibal Pharmacal Company (described in one account as the “predecessor to Neet, Inc.”)—a marriage that lasted slightly past the six-year mark.

Today, the product once known as Neet has been renamed Veet and is owned by Reckitt Benckiser, a British-based company. According to a 2012 press release, the Veet brand, which has expanded into other hair removal products, is used by 30 million women worldwide.

Depilatories: Who Wears Short Shorts?

A major rival in the depilatory market emerged in 1940 when Carter Products introduced a product that would (also!) become one of the world’s best-known brands and inspire one of its catchiest commercial jingles.

The brand name, thought to be a combination of the words “No” and “Hair,” catapulted into advertising history in the mid-1970s when four shorts-clad girls mesmerized television viewers by kicking up their silky smooth (hair-free!) legs while singing, “Who Wears Short Shorts?”

The now-famous chorus continued with, “We Wear Short Shorts. If You Dare Wear Short Shorts, Nair for Short Shorts.”

The lyrics were set to the tune of a 1958 hit aptly named “Short Shorts” by the Royal Teens. The product, of course, was Nair

The lyrics were set to the tune of a 1958 hit aptly named “Short Shorts” by the Royal Teens. The product, of course, was Nair.

An early 1940 print ad hailed the product as an “Amazing New Cosmetic Discovery” that “Removes Hair”; and promised that “you merely spread on Nair and away goes the hair.” The ad continued to say that Nair “looks like your own face cream—and it smells just as nice.”

For a mere 39-cents a tube and a “few brief minutes,” the “hairiest legs or arms become as soft and smooth and inviting as the skin of a baby.” For those still not convinced, a free trial tube was offered to anyone who wrote for one by the November 1, 1940, deadline.

Nair’s 1940 introduction came at an opportune time. While women of the era were keen on wearing stockings—silk had been a staple for years, and the new, wildly popular nylon version had been introduced the previous year—the pending entrance of the United States into World War II was about to change everything.

Silk and nylon, it seemed, were crucial materials in the manufacture of parachutes, tires, tents, airplane cords, ropes, powder bags for navel guns and other war-related items. The U.S. government seized the nation’s supply of raw silk on August 2, 1941 (after all, Japan, the sole supplier, wouldn’t be sending any more shipments to U.S. shores!) and the supply (and ongoing control) of nylon (produced by the U.S.-based DuPont Corporation), followed on February 11, 1942.

American women—and their legs—were left to fend for themselves!

While the popularity of leg make-up or paint enjoyed newfound popularity (women even painted “seams” from their ankles up to emulate real stockings), it was more important than ever for women to sport smooth, hair-free legs.

Bare necessity played a key role in Nair’s early growth. One of the brand’s more recent advertising slogans says it all: “The Less You Wear, the More You Need Nair!”

Today, the Nair brand is owned by New Jersey-based Church & Dwight Co., Inc., which purchased the brand in 2001—the same year that Nair for Men was unveiled to take advantage of the expanding “manscaping” market. In 2008, Nair introduced a spray version that “allows for no-touch application” for “those hard to reach places such as the back.”

The brand’s product lines now include a variety of depilatories in cream, gel and lotion aimed at various body parts, including the face and bikini area.

Tweezers on Steroids

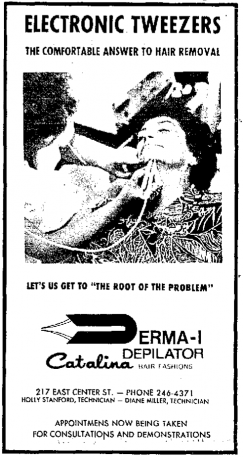

Although waning in popularity, there was a time when “electric” (aka “electronic”) tweezers were all the rage.

Reportedly invented by Elizabeth Fozard, a cosmetologist who patented her invention in 1959 and used it in her own practice only, it wasn’t until the 1970s that electric tweezers seemed to come into their own.

It was then that brands like Depilatron, Removaton, Electroh, Depillex and Derma I Depilator began making a splash as a means of professional hair removal, eventually followed by at-home versions for consumer use.

Hailed by many as a painless alternative to electrolysis, electric tweezers were based on a simple premise: An electric current can travel down an individual hair shaft into the papilla, where it delivers a blow to the hair root. The technician simply grasped an individual hair with the electric tweezers, triggered the release of the current, and waited the required number of seconds for the current to reach its target.

Unfortunately, some advertising and promotional materia ls claimed that the method delivered “permanent hair removal”—which spawned a number of lawsuits by those who disagreed. In a suit filed in November 1976 by the California attorney general and the Orange County (Calif.) district attorney on behalf of three state agencies—including the state board of cosmetology—three firms were charged with violating truth-in-advertising laws.

ls claimed that the method delivered “permanent hair removal”—which spawned a number of lawsuits by those who disagreed. In a suit filed in November 1976 by the California attorney general and the Orange County (Calif.) district attorney on behalf of three state agencies—including the state board of cosmetology—three firms were charged with violating truth-in-advertising laws.

By 1987, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission had charged Removatron with deceptively advertising that its product could permanently remove hair, and required the company to include a disclaimer in its promotional materials. The disclaimer, which was required until the company was awarded a modification in 1991, warned consumers that there was “no reliable evidence that Removatron provides anything more than temporary hair removal.”

Even after the 1991 modification, the FTC held its ground that there was insufficient evidence to support permanent hair removal claims.

The original decision delivered a hefty blow to the industry’s reputation, since Removatron—a venture by entrepreneur Robert Greenberg, the founder of Skechers and L.A. Gear

—accounted for about 80% of the electric tweezer market at that time.

Despite the FTC’s efforts, there was a loophole in their decision that was soon exploited by the electric tweezer industry. Because the original decision prohibited claims only by electric tweezers using an “alternating current” (aka “AC”), there was soon a movement of “direct current” (aka “DC”) tweezers into the marketplace.

Such AC versions are sometimes referred to as radio-frequency (RF) tweezers, high-frequency (HR) tweezers or ultrasonic tweezers; and direct current (DC) as galvanic tweezers.

Even still, electric tweezers no longer hold the market share or promise of supplanting electrolysis that they once did. One of the biggest criticisms by those who question their efficacy is the charge that hair simply cannot (or cannot adequately) conduct electricity.

Today, such tweezers go by various names, in addition to “electric” and “electronic.” Some of the names are a direct tie-in to electrolysis, preceding that word with words like “no-needle,” “non-invasive,” and “tweezer”; or combining the two words to create the word “tweezolysis.”

Wax Away

It may not be the newest kid on the block, but it’s certainly one of the most popular. Waxing, the ancient method of hair removal, continues to hold its own in the modern world as one of the best methods for removing large swaths of hair, relatively quickly and inexpensively—and keeping it off for weeks on end.

Although always a contender, waxing seemed to explode onto the world fashion scene in the mid-1990s when seven Brazilian sisters operating the J Sisters salon in Manhattan, hit a home run when they introduced a bikini wax on steroids—aptly named, the Brazilian.

Although always a contender, waxing seemed to explode onto the world fashion scene in the mid-1990s when seven Brazilian sisters operating the J Sisters salon in Manhattan, hit a home run when they introduced a bikini wax on steroids—aptly named, the Brazilian.

Inspired by the practice of extreme waxing in their native land—where teeny, tiny beach attire rules—the J Sisters (each of whom sports a “J” name) introduced Manhattan women to what it means to take it off, take it all off (well, almost all!), down there.

The Brazilian, which usually consists of removing all but a tiny “strip” of hair in the front and—some say, more importantly—a fair amount in the back, took the city by storm. At a time when thong underwear and bikinis were all the rage, it seemed like the perfect solution to baring it all.

Soon, celebrities like Gwyneth Paltrow, Denise Richards, Naomi Campbell, Cameron Diaz

and Sarah Jessica Parker

, were on the bandwagon; and references were written into such storylines as TV’s Sex and the City

, thus solidifying the craze in the annals of beauty history.

For the J Sisters salon, which now boasts two trendy Manhattan locals, the Brazilian has delivered world-wide fame. The sisters, themselves, have been featured in publications across the globe and on programs such as Oprah. While current figures are unknown, sister Jonice once placed the number of Brazilians performed as “up to 200” daily, with a two-week waiting list. That was back in 1998, only four years after the service was introduced. Today, the J Sisters website simply says that the Brazilian Bikini Wax is the most requested service.

Of course, there’s more to waxing than the bikini area. Today, waxing is considered a viable hair-removal method for the entire body—with some brave (or sorely misguided!) men even opting for head waxing. Ouch, Ouch, and Double Ouch!

Waxing has also become a gateway to body hair maintenance for adolescents and pre-teens, who are increasingly introduced to the treatment by their mothers, as part of their education on proper grooming. Summer camp, here we come!

In addition to the professional waxing available in salons and spas, brands like GiGi, Parissa

, Sally Hansen

and Nair

offer at-home kits for convenience, privacy and affordability.

Sugar Me Smooth

Closely related to waxing, sugaring is believed to have originated in ancient Egypt, where it counted Cleopatra, herself, among its devotees.

Like waxing, sugaring relies on spreading a sticky mixture onto the skin and then removing it quickly (aka ripping it off!)—along with any hair trapped therein.

Unlike waxing, however, sugaring has a number of features that appeal to those looking for a more natural, less painful, somewhat safer, method of hair removal.

Typically made of sugar, lemon juice and water—although other versions do exist—the mixture mimics the consistency of honey and can be applied at a professional salon or at home via products like the Shobha Sugaring Kit and Parissa Chamomile Body Sugar

.

Devotees cite a number of reasons for choosing sugaring: In its purest form, it enlists only food grade ingredients, making it a truly natural option; its use of lukewarm temperatures eliminates the possibility of accidental burning, which sometimes occurs with the higher heats utilized in waxing; and it removes only hair and dead skin cells—not the top layer of the skin, like waxing—which makes it a gentler option and one that can even be used with certain skin sensitivities.

Sugaring mixtures are also water soluble, which means they’re easily removed from skin, clothing and a host of other surfaces!

Threading

There’s hair removal . . . and then there’s threading. Considered an art form by countless devotees, this ancient skill has spread far beyond its Eastern roots into a widening mainstream of Western beauty.

While man y believe threading can be traced more than 6,000 years ago to India, others place the point of origin in countries like Turkey, Egypt and ancient Persia.

y believe threading can be traced more than 6,000 years ago to India, others place the point of origin in countries like Turkey, Egypt and ancient Persia.

Wherever it originated, one thing is certain: It’s played an important role in female culture. In ancient Persia, it was a rite of passage for young girls entering womanhood; and in Iran, it was part of a woman’s bridal preparation.

The concept of threading is somewhat simple: A piece of thread (usually cotton!) is tied together to form a loop, which is then twisted multiple times and manipulated into a “mini lasso” used to trap individual hairs and lift them out, one by one (or row by row!), root and all.

Although threading has traditionally focused on the face—including the chin, upper lip and cheeks—it’s best known for the precision it brings to sculpting beautiful eyebrows, due to its ability to create straight lines and address even the smallest of stubble.

In addition to creating “clean” and “defined” brows, threading is often considered less painful than waxing; a “natural” option, since it uses no chemicals; and a possible alternative to waxing and depilatories for those with skin conditions like acne or rosacea, or sensitivities caused by medications like Retin-A and Accutane. The cost is comparable (and sometimes less!) than that of waxing, and services are performed fairly quickly by technicians whose rhythmic hand movements are like a graceful dance unto themselves.

But when did threading explode onto the Western scene?

Although immigrants have been bringing this ancient skill to Western shores for years, its practice was confined mostly to their own ethnic neighborhoods. Only in the last few decades has threading begun emerging as a mainstream method of hair removal.

One woman who had a lot to do with introducing threading to the United States was Kundan Sarbawal, an Indian immigrant who, along with her two daughters, Suman Patel and Sumita Batra, opened a salon devoted to eyebrow threading in 1988 in the Little India section of Artesia, Calif.

While the salon, called Ziba Beauty, was an instant success among Indian and other Asian women familiar with the technique, its appeal soon began spreading (unexpectedly!) to those of other nationalities and backgrounds, according to the company’s website, which credits the trio with bringing eyebrow threading to the United States.

Today, Ziba Beauty threads nearly 1 million eyebrows a year, boasts 16 locations, thanks in part to its franchise opportunities; and offers other services like waxing and Mehndi (a traditional Indian, non-permanent body art).

But if Ziba Beauty opened the gates to mainstream threading, others soon followed. One such person was Shobha Tummala, a young Indian woman who moved to the United States as a child, but spent summers visiting her grandparents in India, where she was exposed to threading, as well as other Indian beauty customs.

After serving a stint at an Internet start-up—and armed with a degree in electrical engineering from Michigan State University and an MBA from Harvard—Tummala followed her entrepreneurial spirit and dream to expand threading’s reach by opening what may have been Manhattan’s first mainstream threading salon.

Shobha Threading, which started with a single chair that Tummala rented from her SoHo hairstylist in 2001, was designed to offer threading in an environment comfortable to a Western clientele. Less than a year later, Tummala was busy enough to relocate her fledgling business to its own location in the same SoHo neighborhood.

Today, Tummala has three successful Manhattan locations—which also offer sugaring and waxing—and opened a Washington, D.C., location in June 2013. She’s also built a line of products, like the Shobha Sugaring Kit, Shobha Sugaring Gel and Shobha Rosewater Toner, all of which are available in her salons and through other retail outlets.

Her goal is simple—to be the “global destination for hair removal,” according to the Shobha website. No lack of vision, there!

Another Indian woman who has moved threading into the mainstream is Reema Khan, who began offering the service in her Chicago beauty salon in 2003.

After noticing that suburban women were driving into the city for her threading services, she opened a “brow bar” in a nearby Chicago mall.

Using the name S.H.A.P.E.S Brow Bar, Khan began expanding her business, eventually offering franchise opportunities. Today, there are more than 60 locations throughout six states.

Khan, however, has run into a problem that has challenged the expansion of the threading industry. Some states are requiring threaders to be licensed by their boards of cosmetology—a requirement that many deem unfair due to the high cost of cosmetology training and the lack of relevance typically offered in such courses.

In some cases, states have expressed sanitation-based concerns due to the potential reuse of thread on different clients and the threat of staph infections or contagious diseases.

Such was the concern when Arizona issued cease and desist letters to various S.H.A.P.E.S threaders in its jurisdiction. It was only after much legal wrangling that Arizona allowed threaders to forgo a cosmetology license, as long as they met basic health and safety requirements, such as sanitizing their hands and using new thread on individual customers.

Texas, however, hasn’t been so flexible. Although known as a pro-business state, one CNN Money report tells of a man who signed 13 leases and invested a sizable sum of money under the erroneous belief that threaders needn’t hold cosmetology licenses. Once he discovered his error, he appealed to the state for other options, such as a state-mandated course on threading and hygiene. His pleas were unsuccessful, and he ended up closing his shops and losing a claimed $100,000 investment.

At the same time, other states, like California, Colorado, Indiana, Nevada and Utah have exempted threaders from the need to obtain a beauty license.

Despite the challenges, threading seems to have gained a foothold in the Western world, where a growing number of salons are offering the service, and products like the Helix Threadease make do-it-yourself threading easier than ever.

Threading, it seems, is here to stay!

Laser Focused

In today’s modern world, nothing says long-term hair removal like the word “laser.” Indeed. If there’s one method perceived as the gold standard—and cost is certainly part of that description!—it’s laser hair removal.

Although lasers were first developed in the 1960s—Theodore H. Maiman is credited with developing the first laser, using a ruby as a lasing medium—it wasn’t until 1995 that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first laser for hair removal, the Nd:Yag.

Marketed as the ThermoLase SoftLight, the Nd:Yag was “developed by the ThermoTrex Corp. of San Diego, which introduced it through a small number of company-owned spas called SpaThira—eventually numbering more than a dozen and located in such toni locals as Beverly Hills, Palm Beach, Dallas and Manhasset, N.Y.” (See “Bye-Bye Razor! Finding Freedom Through High-Tech Hair Removal.”)

Marketed as the ThermoLase SoftLight, the Nd:Yag was “developed by the ThermoTrex Corp. of San Diego, which introduced it through a small number of company-owned spas called SpaThira—eventually numbering more than a dozen and located in such toni locals as Beverly Hills, Palm Beach, Dallas and Manhasset, N.Y.” (See “Bye-Bye Razor! Finding Freedom Through High-Tech Hair Removal.”)

Its introduction was met with unbridled enthusiasm. In an April 1996 marketing campaign, more than 5,000 (self-described!) hairy women—and men!—responded to an invite by iconic fashion magazine W to help pick the first ThermoLase clients.

A visit to a Spa Thira was a mixture of luxury, as well as a taste of reality: Fresh flowers, Perrier and terrycloth robes and slippers welcomed clients; followed by waxing, the application of a dark, carbon-based lotion (designed to guide the laser to the hair follicle), and then the use of the laser, itself.

Although the ThermoLase SoftLight ushered in the era of modern laser hair removal, it didn’t last long enough to reap long-term benefits.

Indeed. The laser’s use of the carbon-based lotion as a way of attracting and absorbing the laser’s light was soon proven less effective than using the body’s naturally occurring chromophores (i.e., dark hair); and the company’s unsubstantiated claim that the treatment was “permanent” soon attracted the unwanted attention of the FDA and a slew of consumer complaints.

In 1998, only three years after its FDA approval, a class action suit claiming that the ThermoLase SoftLight had been knowingly marketed with false claims of effectiveness, dealt a hefty blow to the young enterprise. Other lawsuits soon followed, and in August 2000, amidst annual losses in the tens of millions and plummeting stock values, the ThermoTrex Corp., along with its subsidiary the ThermoLase Corp., were absorbed by parent company Thermo Electron of Waltham, Mass.

Fortunately, that wasn’t the end of the laser hair removal story.

Additional lasers had been cleared by the FDA as early as March 1997 (e.g., EpiLaser by Palomar Medical Technologies of Beverly, Mass.; and EpiTouch by Laser Industries Ltd. of Tel Aviv) with more following in the months and years thereafter. Each type of laser has its own area of expertise, with factors such as skin tone and hair color and texture, determining suitability.

Today, laser hair removal is one of the top non-surgical procedures performed in cosmetic practices.

In 2005, its popularity as a form of hair removal expanded into the home category with the sale of the first Tria Hair Removal Laser in Japan. Conceived in 2003, this handheld device was developed by the inventors of the LightSheer diode laser, who had set a goal of transforming that machine, which weighed 120 pounds and cost $100,000, into a “handheld laser small enough for at-home use, and capable of delivering the same permanent results.”

In 2008, their product became the first FDA-approved laser for hair removal in the at-home category.

Since then, Tria Beauty has expanded its laser hair removal line, which is currently comprised of its “most advanced” device, the Tria Laser 4X, which offers “professional features and head to toe coverage” and the Tria Laser Precision

, which is designed for “small, sensitive areas like the bikini line and underarms.”

While other, “light-based” hair removal devices have appeared on the market, most, if not all, are based on Intense Pulsed Light (IPL) technology, which utilizes a broad spectrum of light, as opposed to the highly focused, single wavelength utilized by lasers. For many dermatologists and medical professionals, laser light is the more effective, safer technology for hair removal.

The Tria products remain the only FDA-approved lasers for home use.

Rx for Hair Removal

There’s a pill for everything . . . even for hair removal! Or, more accurately, there are a number of pills, and even a cream, that can reduce body hair for some women over time.

Although historical data remains sketchy, the use of prescription medications for hair reduction stretches at least as far back as the 1960s, when Cyrproterone Acetate (aka CPA), an acne drug available in some parts of the world, was used to treat hirsutism.

CPA, and other such drugs, work by addressing various underlying causes of excessive body hair—many of which stem from hormonal imbalances and sensitivities.

Androgens—aka male hormones—are often to blame. For many women, problems arise when androgen blood levels are unusually high, or their hair cells are too easily stimulated by levels considered normal.

Although genetics may be the culprit, that’s not always the case. Certain medications—including birth control pills and steroids—may contain androgens; while others—including some for migraines, seizures, schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and high blood pressure—can cause the body to simply increase its own androgen levels.

One advantage of using prescriptions to reduce body hair is their effectiveness on hair of all colors and textures—a trait not shared by all methods of hair removal. (Laser hair removal, for example, is best known for its success on dark, coarse hair against light skin.)

But while popping a pill or applying a cream may seem like the answer to all hair removal woes, it’s not without its limits: Results may take months to materialize, require ongoing use, prove less effective on some, and effect only new hair growth. What’s more, there may be serious caveats at the end of the supposed rainbow.

Like many medications, those prescribed for hair removal can produce unwanted side effects, including birth defects and fatal liver toxicity. As such, they should be used only after careful consideration and under strict doctor supervision.

It’s also worth noting that drugs prescribed to reduce female body hair may lack approval for such use by various governing bodies, as well as the drugs’ manufacturers. Indeed, many were developed for other purposes and later deemed be effective in reducing body hair, thus leading to their “off label” use.

In the United States, only Vaniqa, a topical cream that reduces female facial hair, is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for any type of prescription hair reduction.

As a final caveat, some medical conditions—like androgen-producing tumors and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)—can also lead to excessive body hair, making it especially important to seek medical advice.

So What’s the Script?

One of the most well-known hair reduction drugs is Spironolactone, an anti-androgen developed by a team of researchers at G.D. Searle & Company in the mid-1900s.

Although some sources trace the drug to the late 1950s, a July 1945 article in The Morning Herald (Hagerstown, Maryland), notes that Aldactone, the brand name for Spironolactone, is “prescribed widely for hypertension”.

Regardless of its origins, the drug has been used extensively as a diuretic and an anti-hypertensive. As early as 1980, however, it was being considered for use against female body hair. Today, it’s cited as one of the most commonly prescribed drugs for such purposes, despite the fact that it lacks FDA approval in that area.

As mentioned earlier, another drug in the war against female body hair is Cyproterone Acetate, a severe acne medication used as early as 1965 to treat hirsutism. Although the FDA withheld approval of the drug for the United States, it’s sold in other countries, including Canada and the United Kingdom, where it’s combined with a contraceptive and marketed under the brand names Diane-35 and Dianette, respectively.

Other anti-androgen drugs include Flutamide (Eulexin), a drug developed by the Schering-Plough Corp. and approved by the FDA in 1989 to help slow the progress of prostate cancer; and Finasteride, which was developed in the early 1990s and marketed first as Proscar, a drug used to shrink enlarged prostate glands, and then as Propecia, a drug for male pattern baldness.

Certain oral contraceptives containing norgestimate or norgestrel are also used as anti-androgens.

When it comes to the FDA, Vaniqa Cream, 13.9%, a topical medication used to reduce unwanted facial hair in women, seems to be the only prescription ever approved for hair reduction—on any body part.

Applied twice daily, Vaniqa (aka eflornithine hydrochloride or eflornithine HCI) works by interfering with an enzyme called ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), which plays a key role in hair growth. Vaniqa does not remove hair, but rather, slows its growth, making it suitable for use with hair removal methods like waxing.

Although eflornithine HCI is considered an “irreversible inhibitor” of ODC, the enzyme is continually regenerating, making daily use of the product necessary for continued results.

Like many hair reduction drugs, Vaniqa lays claim to a colorful history, which includes the development of an oral form of eflornithine as an anticancer agent in the late 1970s; and the licensing of an injectable form to the World Health Organization as a treatment for African Sleeping Sickness in the 1980s.

The Gillette Co. is credited with discovering that topically applied eflornithine HCI inhibits hair growth, securing a patent for such in the 1980s and following it with a formulation patent in 1997.

In July 2000, Bristol-Myers Squibb, in a joint venture with The Gillette Co., was granted FDA approval of Vaniqa. Two years later, the joint venture sold the exclusive worldwide rights and title to Vaniqa to Women First Healthcare for $38.5 million. That ownership was cut short, however, when bankruptcy proceedings led to the June 2004 auction of Vaniqa to SkinMedica for $36.6 million.

Today, Vaniqa is marketed by SkinMedica in the United States, Almirall in Europe, Triton in Canada, Medison in Israel and Menarini in Australia.

Enzymes in the 21st Century

It took 21 Century technology to usher in one of the newest—and surprisingly, one of the most low-tech—methods of long-term hair removal.

The use of enzymes debuted as a professional method of hair reduction with the 2003 launch of the Epilar System, which was developed via a partnership between two Denmark entities, Pedersen’s Laboratories and Cosmedical A/S.

The system , introduced in Northern Europe and expanded to the United States in 2005, worked on a simple premise: The application of proteolytic (protein-dissolving) enzymes to the papilla cells at the bottom of recently exposed hair follicles would hinder hair growth by damaging or destroying said cells.

, introduced in Northern Europe and expanded to the United States in 2005, worked on a simple premise: The application of proteolytic (protein-dissolving) enzymes to the papilla cells at the bottom of recently exposed hair follicles would hinder hair growth by damaging or destroying said cells.

In layman’s terms, it worked something like this: A technician epilated the hair, usually through waxing or sugaring, then applied the enzymatic solution to the skin, massaging it into the newly exposed follicles, so it reached the papilla cells at the bottom, where it began dissolving the hair-producing cells.

The procedure was then repeated at regular intervals as new hair entered the anagen (aka growth) phase, the only phase in which the enzymes were effective.

In its purest form, the use of enzymes is a game-changer: Like electrolysis and laser treatments, enzymes can provide long-term or permanent hair removal. Unlike electrolysis, however, they can be used on large areas of the body in a timely fashion; and unlike laser treatments, they’re more affordable and equally effective on all hair colors and skin tones. (Good news for those with grey hair and tanned or darker skin!)

But how did the idea for Epilar come about? As it turns out, the idea wasn’t a new one. Scientists had been researching the use of enzymes for hair removal as far back as the 1960s, but were stymied by their inability to stabilize the enzymes in their active form. (Inactive enzymes meant an ineffective product!)

While the Epilar System represented a breakthrough in enzyme stability, there were still strides to be made.

Today, Epilar, which relied on the proteolytic enzyme trypsin, is considered a first generation product, having been replaced with the EpilaDerm System, which was introduced in 2007 and relies on a “trypsin complex.”

Cosmedical A/S is no longer in the picture, its partnership with Pedersen’s Laboratories having ended early in the Epilar narrative. Instead, Danlab Ltd., also of Denmark, is Pedersen’s partner in the endeavor and oversees EpilaDerm’s marketing.

According to EpilaDerm.co.uk, the product represents the “latest generation of proteolytic active enzymes for hair growth reduction” and offers the “highest” in-vitro “documented activity” of enzymes.

EpilaDerm utilizes what Danlab Ltd. calls a “universal” sugaring system to epilate hairs. The system, which consists of three customizable sugar pastes designed to sink “deep into the hair follicle,” is based on an application and removal process that follows the direction of hair growth to lessen the likelihood of breakage and capture shorter, harder-to-grasp hairs.

The intended result is a clean, complete removal of individual hairs. Only then can the enzymes, which are applied immediately after epilation, reach their intended target and accomplish their task.

The procedure is typically repeated every two-to-four weeks for facial hair and every four-to-six weeks for body hair for a total of 12-to-18 treatments. Over time, the hair tends to become thinner, slower to grow and more sparsely distributed.

Although the EpilaDerm system is capable of destroying hair-producing cells, DanLab Ltd., markets it as a “long term” hair reduction system, rather than a permanent one, partly because of standards applied to the “permanent” designation, as well as the ability of hair to reappear for a multitude of reasons—such as hormonal changes.

Despite its success, EpilaDerm is not currently in the United States, where another product, also considered second generation Epilar, has taken hold.

That product, called Depilar, is manufactured and distributed by Norlab USA, a San Francisco company founded in 2008 by Peter Lassen, a former partner at Epilar USA. Indeed. Lassen spent almost three years at Epilar, before leaving in February 2008.

According to a Norlab USA spokesperson, Lassen’s experience with Epilar inspired the “creation” of Depilar, which the company calls “superior” to its predecessor, citing efficacy problems due to Epilar’s enzyme instability.

This claim, however, seems to be countered by Kim Andersen, a chief executive officer of Danlab Ltd., who says the “original” Epilar product “never” experienced “shelf-life problems.” He adds, however, that there might be “copies . . . circulating in the USA” that could have such problems.

The Depilar System, which was developed by a team of Danish scientists, is based on the “synergistic effect” of trypsin and chymotrypsin, two proteolytic enzymes which, together, create an “efficacy higher than any other product of its kind on the market,” according to a company press release, which credits the company with being the “first to maintain high enzyme activity in an effective product with a shelf life.”

Depilar is currently sold in 48 countries and works on a premise similar to that of Epilar and EpilaDerm, although, unlike Epiladerm, it does not offer its own epilation system, embracing, instead, waxing, as well as sugaring.

When it comes to hair removal . . . The 21st Century is off to a good start!

Copyright 2013-2020 Jonna Crispens. All rights reserved.

Please Note: This article does not attempt to provide a complete picture of how hair removal beliefs and practices may have played out over time, but rather, to highlight some of the major milestones that have occurred in various civilizations and eras.

{4 Comments}